If we want to bounce back from this global pandemic stronger than we were before, we need to remain optimistic. Although it may not protect you from the coronavirus, optimism can play a role in how your mind and body work during this time. It can be a challenge to be positive about the future when it seems quite bleak. Yet like anything, with some effort, we can train ourselves to be more optimistic, which will provide a range of positive outcomes now and in the future.

What good is optimism?

According to clinical psychologist Dr. Paul Wong (2020), “optimism is the faith or belief in a better future that provides the hope and confidence to realise it despite the uncertainty”. Optimism has a strong relationship with hope, as they are both stable personality traits that reflect a confidence in a positive future. It plays a critical role in resilience as optimists believe that even if the future doesn’t work out, they can bounce back from any disappointment as they expect a better outcome next time… Optimism isn’t about being a ‘Pollyanna’ and ignoring the negative, but giving yourself permission to hope for a better future.

People, who are more optimistic, often have greater engagement in their lives as they put in more effort and try harder, and therefore achieve more. What’s more, optimists are generally happier, more able to deal with stress, and less likely to experience depression, which all have longer-term positive impacts on our mental and physical health. Those who are more optimistic also have better quality and longer-lasting relationships because optimism is a trait we tend to like (i.e. optimists are energetic, happy and easier to be around). Additionally, studies have shown that those who are optimistic about their future, tend to get higher grades, perform better in sports, have a higher income and are more successful in (insurance) sales (Carver et al., 2010).

Optimism is what I call a velcro construct, to which everything sticks

Chris Peterson (2000)

How optimistic are you?

There are two ways to work out how optimistic you are. The first looks at how you think about the future and can be measured by the Life Orientation Test (Scheier, Carver, & Bridges, 1994). The second considers how you explain the past (Seligman, 1990), which is called your explanatory style, and will be covered further here.

Dr. Martin Seligman suggests that when we consider something bad that has happened to us in the past, our brains automatically generate answers to the questions why or what caused that. Our answers can then be assessed along the following three dimensions, which determine our typical explanatory style.

Consider a recent bad event that has happened to you… Did you believe that it was your fault or caused by something external? Was it something you thought of as permanent or changeable? And did you think of the cause of the problem as contained or that it would negatively impact every area of your life?

Seligman believes that optimists consider bad events as external, unstable and specific to that one event.

Depending on how you answered the previous questions and your typical explanatory style, you may be pleased to know that optimism can be learned.

A pessimist sees the difficulty in every opportunity; an optimist sees the opportunity in every difficulty

Winston Churchill

What would an optimist do?

Optimism is a belief system, which means it’s basically a set of thoughts that we have. But we know how powerful our thoughts can be in driving what we do and how we feel. How optimistic or pessimistic we are can therefore impact our resilience and ability to overcome struggle through difficult times.

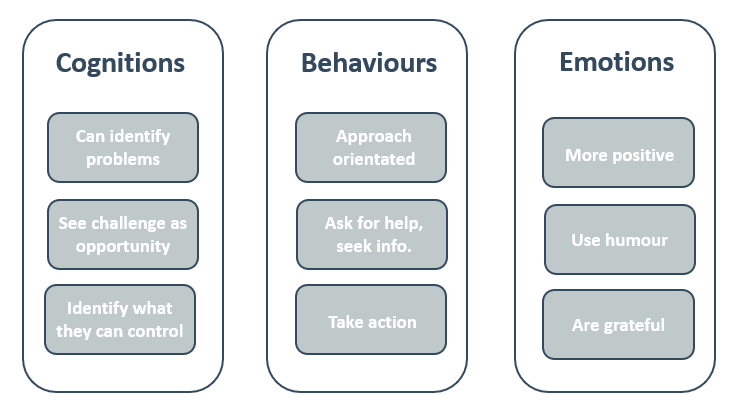

Below is a snapshot of the variables that optimists typically engage in, that maybe pessimists do not (Positive Psychology Center, University of Pennsylvania). Perhaps it is these thoughts, behaviours and emotions that are driving some of the great outcomes associated with optimism.

What’s the right dose of optimism?

Like anything, too much optimism can be harmful. For example, having an optimism bias can cause people to have a false sense of security and underestimate potential risks to themselves, which is usually common in smokers or gamblers i.e. “it won’t happen to me”. Being too optimistic at work can also result in poor planning, a failure to source necessary resources and a reliance on hard work and determination (Compton & Hoffman, 2012; Peterson, 2000). And of course, there is always a time and place for some mild pessimism…

Optimism could be just as important as hand sanitiser for us right now. Although our current circumstances seem pretty negative, we can still be hopeful about a better future. Being optimistic can take a lot of time and effort but the payoff will be worth it!